Distinguishing causality from correlation -- What factors drive SARS-CoV-2 infection and Covid-19 Severity?

February 05, 2021

Written by Annika Faucon and Shea Andrews, PhD

Edited by Kumar Veerapen, PhD

Note: This blog is intended for an audience of scientists and contains terminology specific to the field of genetics & genomics.Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly transmissible and pathogenic virus that emerged in late 2019 and as of February 2021 has resulted in more than 2.4 million deaths (further reading: Dong, Ru, and Gardner, 2020). The threat SARS-CoV-2 presents is not uniform; certain pre-existing health issues predispose individuals to a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or COVID-19 severity (further reading: Williamson et al., 2020).

It remains important to distinguish characteristics associated with observing an infectious disease from those that increase susceptibility or severity.

There are still a few questions that remain to COVID-19 infections such as: what are these, at times known and at other times unknown or hidden, factors that increase an individual’s risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization due to COVID-19, or critical illness? How can we rule out other causes for this severity that are associated with the hidden factors but not caused by them?

It is not difficult to identify risk factors that correlate with an increase (or decrease) the risk of infection or the severity of disease.To do this, scientists use observational studies that compare risk factors in people who have a disease against those who do not, These types of studies have identified a number of risk factors associated with COVID-19 severity including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and kidney disease (further reading: Williamson et al., 2020, Jain et al., 2020). Even with the known correlation of these conditions, it is difficult to disentangle whether the factor itself is causing increased susceptibility or severity, or whether other unseen forces associated with the disease are driving the risk.

Here is where Mendelian Randomization (MR) and the work of Shea Andrews, PhD, a scientist with the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, comes in. Dr. Andrews led a team of the HGI researchers that used MR to explore how the genetic liability of 43 traits, including anthropomorphic measures (BMI, height, etc.), demographic measures, as well as pre-existing diagnosed disease, impacts the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 severity.

What is Mendelian Randomization?

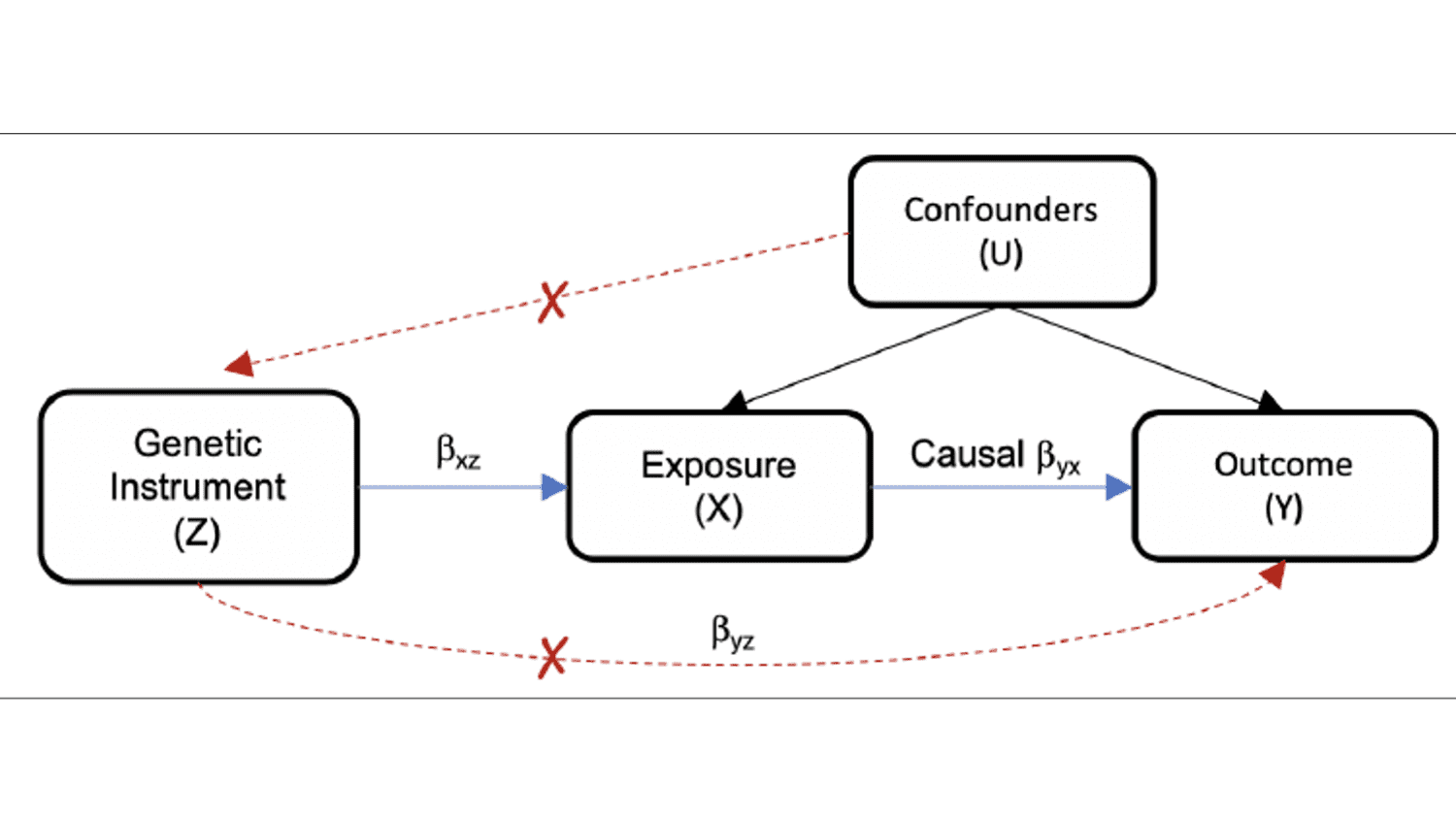

Mendelian Randomization (MR) is a research method that incorporates genetic information into a traditionally epidemiological framework with the goal of distinguishing causality from correlation. The method, first proposed in 1986, is valued for being less susceptible to confounding because it is far less likely to be influenced by lifestyle or environmental impacts or to reverse causation because an individual’s genetic information is determined at conception (further reading: Katan et al., 2004 ).

Conceptually, MR is a ‘natural’ implementation of a Randomized Control Trial (RCT). In an RCT, participants are randomized to two or more groups, assigned with different treatment exposures, and assessed using some measured response. By comparison, the independent assortment of chromosomes randomly distributes exposure, causing differences in exposure and measured response. Furthermore, the genetic code is static after birth, so the influence of the exposure on an outcome is assessed by evaluating the impact of genetic variants on exposure and on an outcome variable (further reading: Davies et al., 2018).

In reality, there are important differences between RCTs and MR. Firstly, the randomization of exposure in RCTs is assigned by experimenters. In MR, however, randomization is confounded by LD, population stratification, and non-random mating. In RCTs, the timing of intervention and follow-up are predetermined (prospective), limiting reverse causality. By contrast, MR may not affect the allocation of alleles, but it may affect inclusion in the study via survivor bias or other factors. Justifying causality is easier in RCTs because differences in response follow intervention experiments, whereas in MR causality claims are less robust.

The Bradford Hill criteria offers empirical guidelines for using MR to justify the implementation of an RCT. The criteria include that the exposure must precede the measured outcome (temporality), dose-response relation and specificity in exposure-outcome relation (further reading: Burgess et al., 2016, Haycock et al., 2016. In addition, valid causal inference requires that the association between a genetic variant and outcome is mediated only through the hypothesized exposure, i.e. that the genetic instrument is associated with the exposure and is independent of the outcome when conditioning on the exposure and confounders, and that the genetic instrument is not associated with confounders of the exposure-outcome association (Figure 1). In addition, the genetic instruments should be well-defined, with a large effect and high penetrance (further reading: Haycock et al., 2016).

A common approach is to use multiple methods with distinct assumptions and blindspots. The idea here is that any associations identified with all methods are less likely to be spurious. For example, the inverse-weighted variance method assumes that the genetic variants (instrument variables) cause the outcome only through the proposed exposure (no horizontal pleiotropy). A weighted median approach proposes that at least half of the instrument variables are valid. MR Egger does not assume the outcome is affected by only the exposure (further reading: Haycock et al., 2016). However, by being more robust to violations of the assumptions of MR, these methods also have a reduced statistical power to identify a true causal effect.

How did we use Mendelian Randomization in the COVID-19 HGI data?

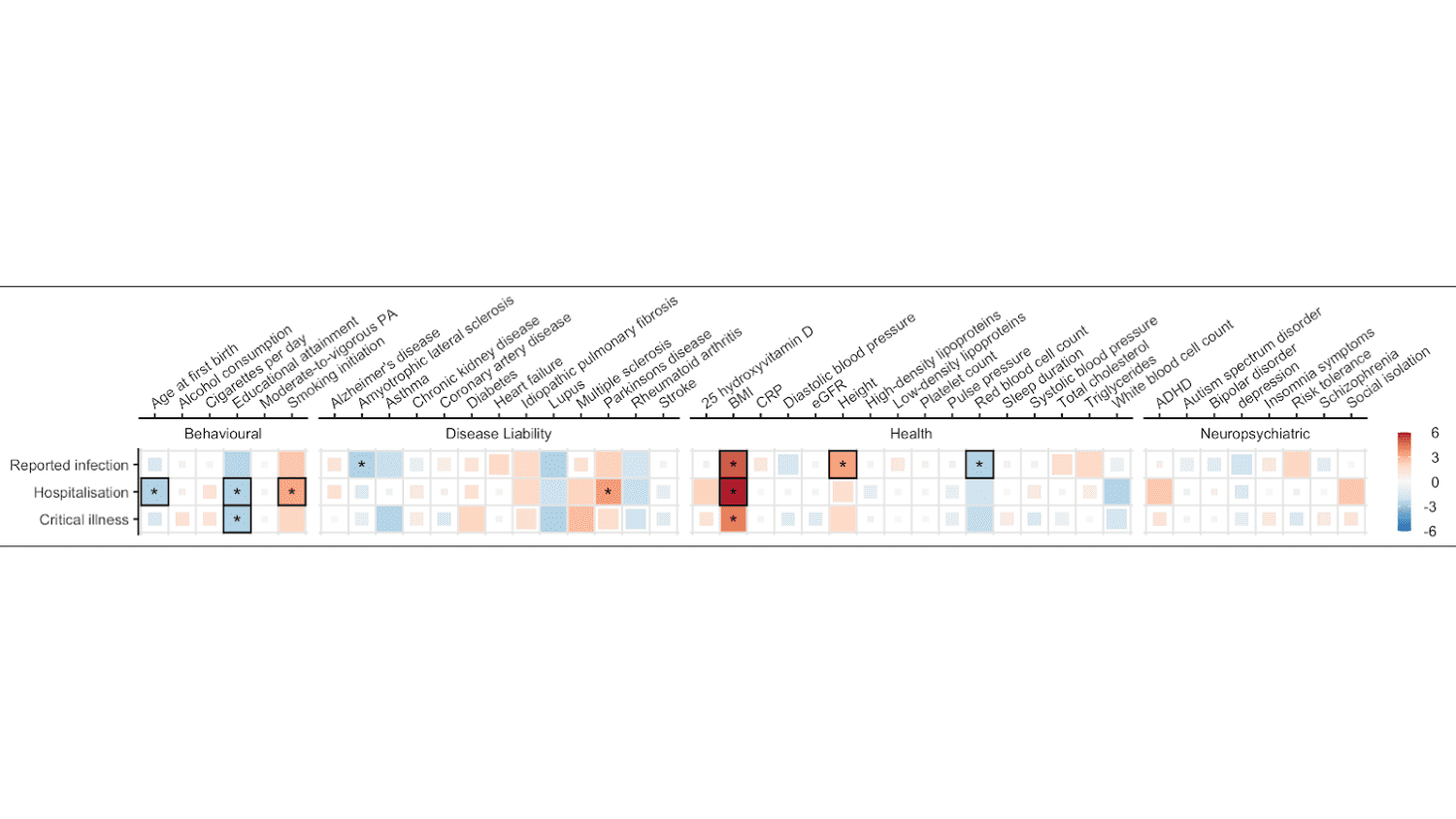

Dr. Andrews and his team used 5 methods to explore the relationship between the traits and SARS-COV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity (hospitalization and critical illness): Inverse-Variance-Weighted, MR Egger, MR PRESSO, Weighted Mean Estimate, and Weighted Mode-based Estimator (further reading: Andrews et al., 2021). After correcting for multiple testing, statistically significant robust causal estimates between 6 traits and SARS-COV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity were identified (Figure 2).

Genetic liability to higher BMI was associated with increased risk of both reported SARS-COV-2 infection and COVID-19 hospitalization. Genetic liability for higher educational attainment was associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 hospitalization and critical illness. Genetic liability for smoking was associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 hospitalization. Genetically predicted later age at first birth (having your first child at a later age) was associated with a reduced risk of COVID-19 hospitalization. Genetically predicted height was associated with an increased risk of SARS-COV-2 infection, while increased red blood cell count was associated with reduced risk.

Though imperfect, the use of MR in conjunction with other study designs such as observational studies can be used to distinguish causation from correlation and will likely aid in prioritizing action on genetic and mechanistic disease elements to ultimately reduce SARS-COV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity. In particular, obesity has been implicated by both approaches as an important risk factor in determining an individual’s likelihood of having severe COVID-19.

“As an internist, disease prevention is an important part of my clinical practice,” says Jonathan Mosley, MD, PhD, who teaches and practices medicine at Vanderbilt University, and specializes in epidemiology and molecular biology, “Methods such as MR, which can quickly identify important risk factors, are very useful to prioritize risk-reduction approaches among my patients.”

The MR method can also be used to identify traits that are unlikely to have a causal role in COVID-19 severity. For example, the MR results do not support a causal role between type 2 diabetes COVID-19 severity, which has been reported in observational studies, potentially due to confounding between type 2 diabetes and obesity in observational studies. Similarly, it has been suggested that taking vitamin D supplements may reduce the risk of COVID-19 severity, but the MR results indicate that individuals with naturally higher levels of vitamin D do not have a reduced risk of COVID-19 severity. This suggests that taking vitamin D supplements is unlikely to prevent severe COVID-19.

Overall, these findings further contribute to our understanding of how various traits can impact SARS-COV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity, and can be used both to identify those individuals most at risk of developing complications from COVID-19 and to inform the changes that can provide protection against the infection.

“I am very heartened to see that a number of modifiable risk factors, such as elevated weight and smoking, are among the associations identified in this study,” Dr. Mosley added, “These data provide one more set of data that I can leverage to persuade my patients to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors.”

NOTE:

For studies contributing to the final freeze 5 meta-analysis, please refer to the RESULTS page. This data is currently unpublished and was presented at the COVID-19 HGI results update meeting on January 25th, 2021 (slides and presentation found here ). The results will be published the COVID-HGI efforts and will be made available in the near future.

We would also like to thank the significant contribution of the Mendelian Randomization team:

Eirini Marouli, PhD, Mari Niemi, PhD, Laura Sloofman, PhD, J.E Savage, PhD, P.R Jansen, PhD, Camelia Minica, PhD, Joseph Buxbaum, PhD, and Shea Andrews, PhD.

Contributing Studies that allowed this fantastic work to be completed can be found here